Mid-term Review Topics

- Python/Programming

- REPL, Notebook, Module

- Assignment

- Data types (

int,str,float,tuple,list,set,dict) - Constants (

True,False,None) - Control Structures

(

if/elif/else,for,while, comprehensions) - Built-in Functions (

print(),len(),range(),open(),enumerate(),any(),all()) - Functions (arguments, default arguments,

return) - Raw data (

open(),str.encode(),bytes.decode(),urllib.request.urlopen().read()) - Pandas (

read_csv(),read_excel,to_csv(),to_excel)

- NLP/CL

- Basic tokenization

- Text normalization (purpose, kinds of normalization)

- Types vs Tokens

- Frequency Distributions, Conditional Frequency Distributions

- Text corpora (Gutenberg, Brown, annotated corpora)

- Lexical resources (word lists, stopwords, pronouncing dictionaries, WordNet)

- Software Engineering

- Paths and folders

- Git (purpose, usage)

- Efficiency (e.g., which function is faster)

- Mutability of data structures

- Side-effects of functions

- Unicode (purpose, what is it)

- Files and Streams (purpose, difference from strings/bytestrings)

- Virtual Environments (purpose, troubleshooting)

Learning Objectives

Python/Programming

This category is for programming concepts, techniques, and structures as used in Python.

Modes of Programming

Python is a very flexible language that can be used in multiple ways.

REPL

REPL (Read-Evaluate-Print-Loop) describes the way the computer

operates an interactive interpreter such as Python’s IDLE

interpreter. The computer reads what the user entered, evaluates it,

prints the output, and loops (starts this process again). When you see

code written with >>> on the left side, it is

showing what you would see in an interactive interpreter:

>>> print("hello")

helloYou can start an interactive interpreter by running the Python command in a terminal without any arguments:

$ python Python 3.8.2 (default, Jul 16 2020, 14:00:26)

[GCC 9.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>The REPL mode of Python is useful for quick experiments and debugging, but it is not easy to revise what has been entered so it is not convenient for larger programs.

Module

Perhaps the most common way to write Python code is in a

module. A module is just a .py file containing

Python code. The file is saved on the computer and it is not run until

it is loaded and processed by a Python process. Modules meant to be

imported by other modules are generally called libraries, while

modules meant to be run directly are called scripts. Imagine

you had a file hello.py with the following contents:

print('hello')You can then run this script at the command line and see its output

as follows (depending on your system and environment, the

python3 command may be python,

py, or something else):

$ python3 hello.py

helloUsing modules to write Python code is the most versatile mode and is recommended for most uses.

Notebook

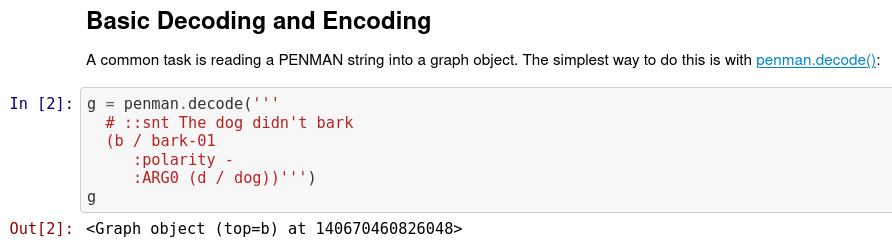

A mode of using Python popular for demonstration or pedagogical purposes is the notebook. It mixes human language text with Python code and sometimes provides a more friendly view of the output (e.g., rendered charts and tables). This style of programming is called literate programming. It looks something like this:

Expressions, Statements, Definitions

Assignment

>>> x = 3 # assign the value 3 to the variable named 'x'

>>> x = x + 1 # evaluate the expression 'x + 1' then assign its result to x

>>> x

4

>>> x += 1 # shorthand for the above

>>> x

5

>>> x = 'foo' # variables can be reassigned to values of a different type

>>> x.upper() # an expression involving the variable does not change its value

'FOO'

>>> x

'foo'

>>> x = [1] # ...

>>> x.append(2) # unless the value is mutable

>>> x

[1, 2]

>>> x = x.append(3) # be careful not to reassign to function that return None (don't do this)

>>> x is None

TrueFunctions

def myfunction(x, y, z=0): # define a function named 'myfunction' with 3 parameters;

# x and y are required, z has a default value so it is optional

return x * y * z # return a value so the caller can make use of it

# if there is no return statement, the function returns NoneOnce a function is defined, call it by its name:

>>> myfunction(1, 2)

0

>>> myfunction(1, 2, 3)

6Data Types

int

Integer types represent positive or negative whole numbers.

>>> 1024 # literal integers are base-10

1024

>>> int(3.14159) # int() casts floats to integers

3

>>> int('101') # int() casts strings to integers

101

>>> int('101', 2) # an explicit base can be given

5

>>> 20 // 3 # floor division drops any remainder

6float

Floating-point numbers represent numbers with a fractional component.

>>> 3.14 # literal floats include a decimal

3.14

>>> 6.02e23 # and/or an exponent

6.02e+23

>>> float(3) # float() casts from integers

3.0

>>> float('3.14') # and strings (but only base-10)

3.14

>>> 20 / 3 # regular division results in a float

6.666666666666667

>>> 20 / 5 # even when there's no remainder

4.0str

Strings are sequences of characters.

>>> 'a string' # strings are surrounded by single quotes

'a string'

>>> "another string" # or double quotes

'another string'

>>> '''yet

... another''' # or three single/double quotes (newlines allowed)

>>> 'もう一つ' # unicode is ok

'もう一つ'Useful string methods:

- str.split() – return the list of tokens in the string

- str.lower() – return the string with all cased characters downcased

list

Lists are mutable sequences of values.

>>> x = [] # make an empty list

>>> x = list() # this works, too

>>> x.append(1) # add a single value

>>> x.extend([2,3]) # add multiple values

>>> x

[1, 2, 3]

>>> x[1:] # slice from the 2nd element

[2, 3]

>>> x[:-1] # slice until 1 before the last element

[1, 2]

>>> len(x) # find how many elements are on the list

3

>>> x.count(3) # count how many times a particular element occurs

1

>>> 4 in x # use 'in' to check for membership

Falsetuple

Tuples are immutable sequences of values.

>>> () # make an empty tuple

()

>>> tuple() # or use the function

()

>>> (1) # but this doesn't work (it looks like an expression)

1

>>> 1, 2 # use commas to create tuples in general

(1, 2)

>>> 1, # even for single items

(1,)

>>> (1, 2) # but often we need parentheses around them

(1, 2)

>>> x = tuple([1, 1, 2, 3]) # create tuples from an iterable

>>> x[1:-1] # slicing works as expected

(1, 2)

>>> x.count(1) # many list operations work on tuples (but not mutating ones)

2set

Sets are containers of unique values.

>>> set() # use the function to create an empty set ('{}' creates a dictionary)

set()

>>> {1, 2} # Use braces with comma-separated values to create non-empty sets

{1, 2}

>>> {1, 1, 2, 3} # repeated values are dropped

{1, 2, 3}

>>> x = {1, 2}

>>> x | {3} # | is the operator for set-union

{1, 2, 3}

>>> x & {2} # & is the operator for set-intersection

{2}

>>> x.add(3) # use add() to add a single value

>>> x.update([3, 4]) # use update() to add multiple values (duplicates still dropped)

>>> x

{1, 2, 3, 4}

>>> 2 in x # check for membership

Truedict

Dictionaries are much like sets but they associate keys to values.

>>> {} # create an empty dict with {}

{}

>>> dict() # the function works, too

{}

>>> {'a': 1, 'b': 2} # keys ('a' and 'b') map to values (1, 2)

{'a': 1, 'b': 2}

>>> d = {'a': 1}

>>> d['b'] = 2 # assign a single key to a value

>>> d.update({'c': 3, 'd': 4}) # update() to assign multiple keys to values

>>> d['c'] # retrieve the value associated with a key

3

>>> d['b'] = 1 # keys are unique; here 'b' is reassigned

>>> d # but values need not be unique

{'a': 1, 'b': 1, 'c': 3, 'd': 4}

>>> len(d) # len() gets the number of keys

4

>>> list(d) # list(d) returns the list of keys

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

>>> 'b' in d # check for membership of keys

True

>>> 1 in d # cannot check for membership of values this way

FalseConstants

A constant is a special type of variable whose value cannot be changed. However, we don’t really use constants in Python since any variable can be reassigned. It is good to know, however, which variable names (like ‘list’, ‘dict’, etc..) should be avoided so you don’t accidentally reassign key functions. Naming constant variables in all capital letters is a convention to separate them from ordinary variables, however, it does not actually prevent reassignment.

True, False

Boolean operators that identify values.

None

An operator that identifies presence/absence.

Control Structures

if

An if statement is used for a conditional

block—code that is executed only if a condition is true. See the

Python Tutorial’s section on if

Statements.

Only one thing below will be printed:

word = 'Dog'

if word in vocabulary:

print(word, 'exists in the vocabulary')

elif word.lower() in vocabulary:

print(word, 'exists in vocabulary when case-normalized')

else:

print(word, 'does not exist in vocabulary')Note that if you use multiple if statements instead of

elif or else, they will be attempted

regardless of whether the previous conditions were true. In the

following, both will print if both 'Dog' and

'dog' are in the vocabulary.

word = 'Dog'

if word in vocabulary:

print(word, 'exists in the vocabulary')

if word.lower() in vocabulary:

print(word, 'exists in vocabulary when case-normalized')for

A for statement (also called a for-loop) loops over each

item in an iterable. This generally means the loop is bounded by the

number of items in the iterable, and it’s used when the iterable items

themselves are used inside the loop. See the Python Tutorial’s section

on for

Statements.

numbers = [1, 2, 3]

for number in numbers:

square = number**2

print(f'the square of {number} is {square}')while

A while statement (also called a while-loop) loops as

long as a condition is met. This condition can be just about anything,

and sometimes it is True, meaning an infinite loop. See the

Python Tutorial’s example of while

statements. While-loops are often used when the number of iterations

is not fixed or known in advance, or when there is no iterable whose

items are used inside the loop.

# print Fibonacci numbers less than 100

a = 0

b = 1

while a < 100:

print(a)

tmp = b # temporary variable for the old value of b

b = b + a

a = tmpComprehensions

Built-in Functions

print()

len()

range()

enumerate()

any()

all()

open()

Raw data

open()

str.encode()

bytes.decode()

urllib.request.urlopen()

Pandas

Pandas is a library for working with dataframes, a table-like structure that allows for rapid calculations. It also helps us to organize data into a human-readable structure. You can used Pandas by importing it and initializing a dataframe:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame()You can also use pandas to read and write character-delimited files or excel spreadsheets:

df = pd.read_csv('randomfile.csv', delimiter="\t")

df = pd.to_csv('randomfile.csv', sep="\t")

df = pd.read_excel('randomfile.xlsx')

df = pd.to_excel('randomfile.xlsx')NLP/CL

This category is for concepts and techniques related to natural language processing or computational linguistics.

Concepts

types-vs-tokens

tokenization

normalization

Frequency Distributions

Conditional Frequency Distributions

Text Corpora

Lexical Resources

Tools

NLTK

Software Engineering

This category is for practices of software engineering as well as programming concepts that are relevant to programming languages beyond Python.