Learning Objectives

- Concepts: encodings streams open urllib formatting byte strings with statements

(color key: Python/Programming NLP/CL Software Engineering)

tl;dr

For this week, I want you to understand these two main points before class.

Strings in Python are abstract sequences of Unicode code points (generally, every character gets one code point), but whenever these strings leave Python (e.g., get written to disk or transmitted over a network), they must be encoded into a sequence of bytes, and there are different encodings for doing so. Practically speaking, you should have an idea about what is happening here:

>>> 'café'.encode('utf8') b'caf\xc3\xa9'With strings, lists, and other basic data types, you have the entire contents at once, so you can query the size of the data structure and access any part at any time. When reading files or other streams, you are using a buffer, which only provides a window into part of the file at a time. The size of a buffer is unknown, and access is sequential. In practice, you should understand how to use the open() function to read and write files:

>>> with open('some-file.txt') as fh: ... contents = fh.read()

Reading

- Encodings

- Streams

- String Formatting

Additional Information

Encodings

(XKCD on Unicode: here, here, here, here, and here)

So far we’ve been working with strings and data in an idealized way but outside of Python the data is encoded into sequences of bytes (1s and 0s). There are different ways (encodings) string characters can be put into bytes, so the same string in Python may be a different sequence of bits on disk. Observe below how the last letter of café is encoded differently by the UTF-8 and Latin-1 encodings, and it cannot be encoded at all by the ASCII encoding:

>>> 'café'.encode('utf8')

b'caf\xc3\xa9'

>>> 'café'.encode('latin-1')

b'caf\xe9'

>>> 'café'.encode('ascii')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

UnicodeEncodeError: 'ascii' codec can't encode character '\xe9' in position 3: ordinal not in ran(128)Where are the 1s and 0s? It wouldn’t be very useful to just print the

binary sequence directly, so Python prints non-ASCII or non-printable

characters with escape sequences. \xe9, for instance, is

the hexadecimal

sequence e9, which in a base-10 (decimal) number system has

the value 233, corresponding to the 233rd Unicode codepoint.

Reading from the Web

You can use Python’s urllib.request module to access data on the internet:

>>> import urllib.request

>>> the_iliad_url = 'http://gutenberg.org/files/6130/6130-0.txt'

>>> with urllib.request.urlopen(the_iliad_url) as f:

... the_iliad_raw = f.read()This gets you the byte string of the book (note the b

before the string):

>>> the_iliad_raw[0:60]

b'\xef\xbb\xbfThe Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad, by Homer\r\n\r\nThi'You still need to decode this to a unicode string, and for that you need to know the encoding. There are 3rd-party projects that try to automatically determine the encoding, such as the popular chardet. There is also a 3rd-party project requests, which has a nicer interface and more features for making web connections:

>>> import requests

>>> response = requests.get('http://gutenberg.org/files/6130/6130-0.txt')

>>> response.text[0:60]

'The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad, by Homer\r\n\r\nThi'The requests package detects the encoding of the file either from information provided by the web connection or from chardet’s analysis. Character detection is not perfect, though, as can be seen by the first few characters that were improperly decoded, but the rest should be fine.

String Formatting

For historical reasons, there are many ways to construct, or format, strings in Python. Below is a short, opinionated overview.

Manual Formatting

You can format strings by concatenating all the parts together:

>>> age = 5

>>> pi = 3.14159265

>>> name = 'Kim'

>>> print('At age ' + str(5) + ', ' + name + ' could recite 6 digits of pi: ' + str(round(pi, 5)))

At age 5, Kim could recite 6 digits of pi: 3.14159Don’t do this! It’s ugly and inefficient. However, there are times when the dedicated formatting tools are not sufficient and some manual formatting is required.

Old (printf) Style Formatting

You might see code like this:

>>> print('At age %d, %s could recite 6 digits of pi: %.6g' % (age, name, pi))

At age 5, Kim could recite 6 digits of pi: 3.14159Don’t do this! It’s outdated and there are better alternatives. Don’t even bother learning it, but it’s good to recognize that this is a way of doing string formatting because some people still use this form.

str.format()

The printf-style formatting was supplanted by

str.format():

>>> print('At age {}, {} could recite 6 digits of pi: {:.6g}'.format(age, name, pi))

At age 5, Kim could recite 6 digits of pi: 3.14159At first glance this doesn’t seem much better than the previous version, but it’s more capable in complex cases. Also, the placeholders can be given names:

>>> print('At age {age}, {name} could ...'.format(age=age, name=name))

At age 5, Kim could ...f-strings

The newest method of string formatting uses a similar syntax to str.format(), but does formatting in-place using available variables:

print(f'At age {age}, {name} could recite 6 digits of pi: {pi:.6g}')These f-strings (“formatted string literals”) are often the most readable and the most efficient, but they are evaluated in-place, meaning that the variables must be defined when the string is encountered. This is in contrast to str.format(), which can be formatted later:

>>> fmt = '{name} says, "hi"'

>>> # ... later

>>> print(fmt.format(name='Sandy'))

Sandy says, "hi"Lecture

Review of homework 5

In-class walkthrough of concepts

Testing Your Knowledge

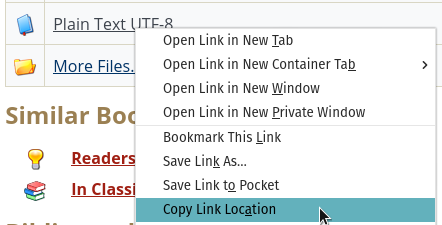

Go to http://gutenberg.org/ and find an ebook. Look for the “Plain Text” link, then right click to get the URL of the file (your browser may look different):

Now paste the URL into your code file as a string. Use this string to

download (with urllib.request or requests, as

you prefer) the file.

Determine what is the encoding of the file, and use that information

to decode the raw byte-string (for requests, use

response.content instead of response.text to

get the byte string).

Once you’ve decoded the contents to a string, write the string to a file on your computer. You might use a different encoding than the one you used to decode, but not all encodings will be compatible, depending on the characters used in the file.

Once the file is written, try to open it again in Python.

For further practice, review section 3.1 from the NLTK book and find out how to tokenize the full string of the book into words.